INTEGRATED PROJECT DELIVERY

A delve into the success of Suffer Health facility

Suffer Health is a communitybased healthcare provider, which works on a nonprofit basis. The 1994 Northridge earthquake resulted in a design and construction programme of US$5.5bn for Suffer. This included parking structures, acute and non-acute healthcare facilities and medical buildings. To successfully deliver the project, Suffer’s facility planning and development department (FPD) was assigned to manage the task of timely delivery of the project without any health and safety incidents and claims (Oakland, JS & Marosszeky, M, 2017; Lichtig, 2005).

The integration of BIM and lean methodology resulted in following benefits as reported by the owner (Dave et al.,2013):

- Six weeks earlier completion date.

- A reduction of 15% in rework.

- No cost overruns.

Model-based estimation (MBE)

A team at Suffer Health employed target value design at Eden Medical Center and followed lean and integrated procedures. The multi-disciplinary team of architects, BIM engineers and estimators generated cost estimates every two weeks by adopting automation. Rapid cost feedback was achieved by linking BIM elements to assembly data in an estimation software. By using quantity parameters from the BIM, the team was able to estimate labour, material, equipment and other associated costs (Fischer,2017).

This BIM-derived estimation is also known as 5D and it uses database in the background of BIM to link components of a model to unit cost (Hardin, 2015) and several BIM tools offer ability to automate the estimate (Dave et al., 2013). By using a shared parameter.txt file in Revit, the team at Suffer Health managed to facilitate the quantity takeoff and estimating process (Eastman et al., 2011).

True collaboration was another main goal of Suffer Health. Contractors were involved in the early stages to assist with design. The integration of various models ensured accurate collaboration and less chances of errors (Eastman et al., 2011; Fischer, 2017). Using ‘big rooms’ and online collaboration (Webex and GoToMeeting), different teams were able to do weekly revisions using Navisworks (Eastman et al., 2011). Suffer Health implemented lean planner system (LPS) and organised training sessions for the staff to familiarise themselves with LPS tools (Lichtig, 2005; Oakland, J.S, & Marosszeky, M, 2017).

This BIM derived estimation is also known as 5D and it uses database in the background of BIM to link components of a model to unit cost and several BIM tools offer ability to automate the estimate.

A web-based portal was also created to help team members share information and tools (Lichtig, 2005). This big room concept had a big influence of Tidhar to adopt to move to big room designing (Sacks, 2017).

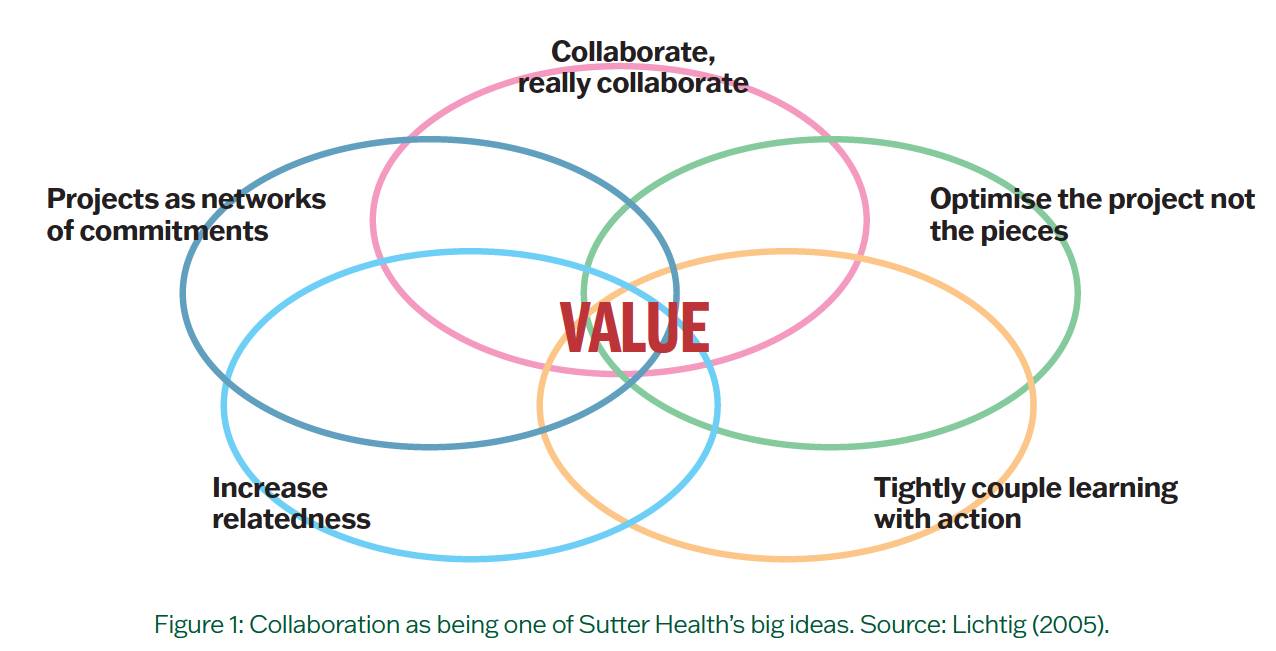

Suffer Health believes that true collaboration occurs when all parties are given equal opportunities, and they focus on exploring and defining issues rather than criticising someone’s solution (Lichtig, 2005). It was the usefulness of this collaboration that saw the teams manage to prevent a major issue by identifying early design problems due to beams causing collisions (Tiwari et al., 2009).

Laser scanning was used to ensure as-built structures matched with the design (Oakland, JS & Marosszeky, M, 2017; Fischer, 2017). This method was also adopted to scan all the walls and ceiling utilities before enclosing them. Photogrammetry was also combined with laser scanning to create an up-to-date model for the client (Dave et al., 2013).

Suffer Health used an 11 party IFOA for the first time, which required the owner, architects, designers, contractors, lean consultants and other teams to be cosignatories of the agreement. This IFOA included all key project members and team members were required to work in a collaborative environment by making use of lean technologies such as BIM. These signatories share the risk or rewards depending on the outcome of project against target cost (Eastman et al., 2011). This allowed Suffer Health to come out as a full IPD contract, which made a significant difference. Stuart Eckblad of UCSF Health has provided an interesting example of a traditional project and then adding IPD elements by using risk/reward provisions.

He states:

“And what was interesting is a result of the traditional process for the first 18 months, we were over the budget and having to consider dropping scope. About three months after we were able to get everyone on board (with interlocking contracts), we actually had a huge reduction in cost and got all of our scope.” (Fischer, 2017).

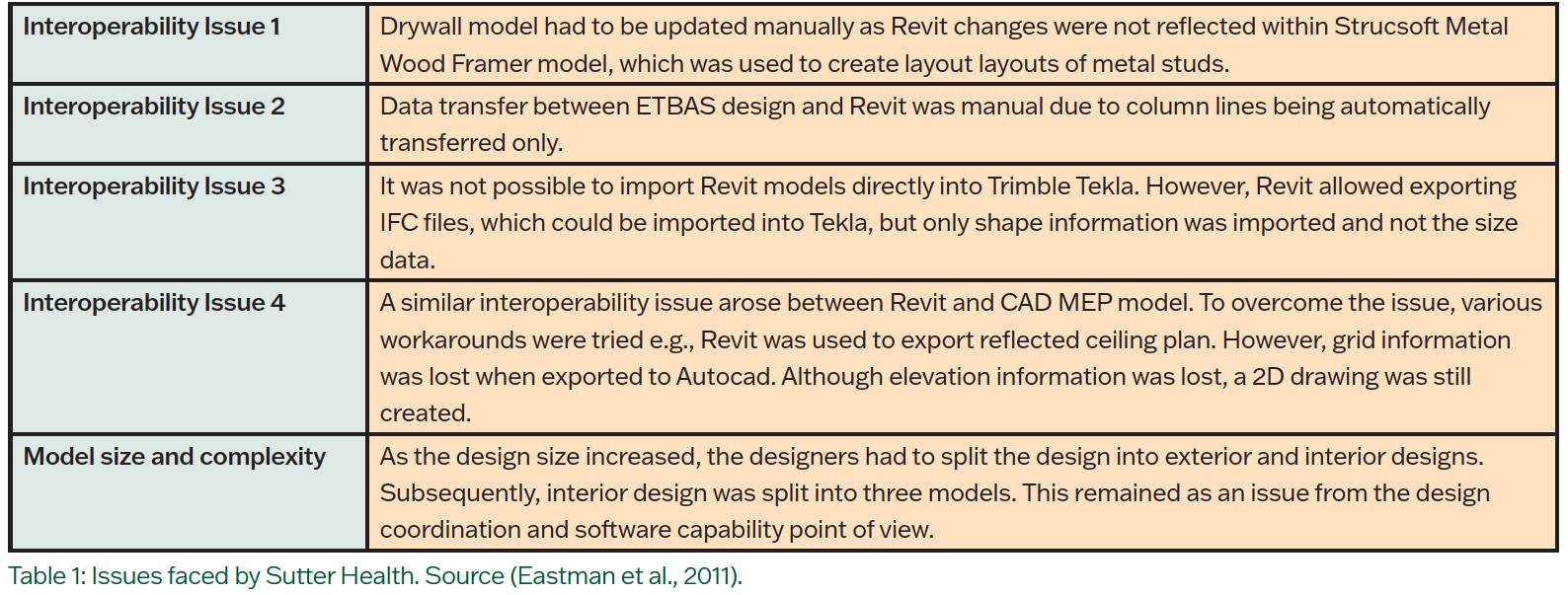

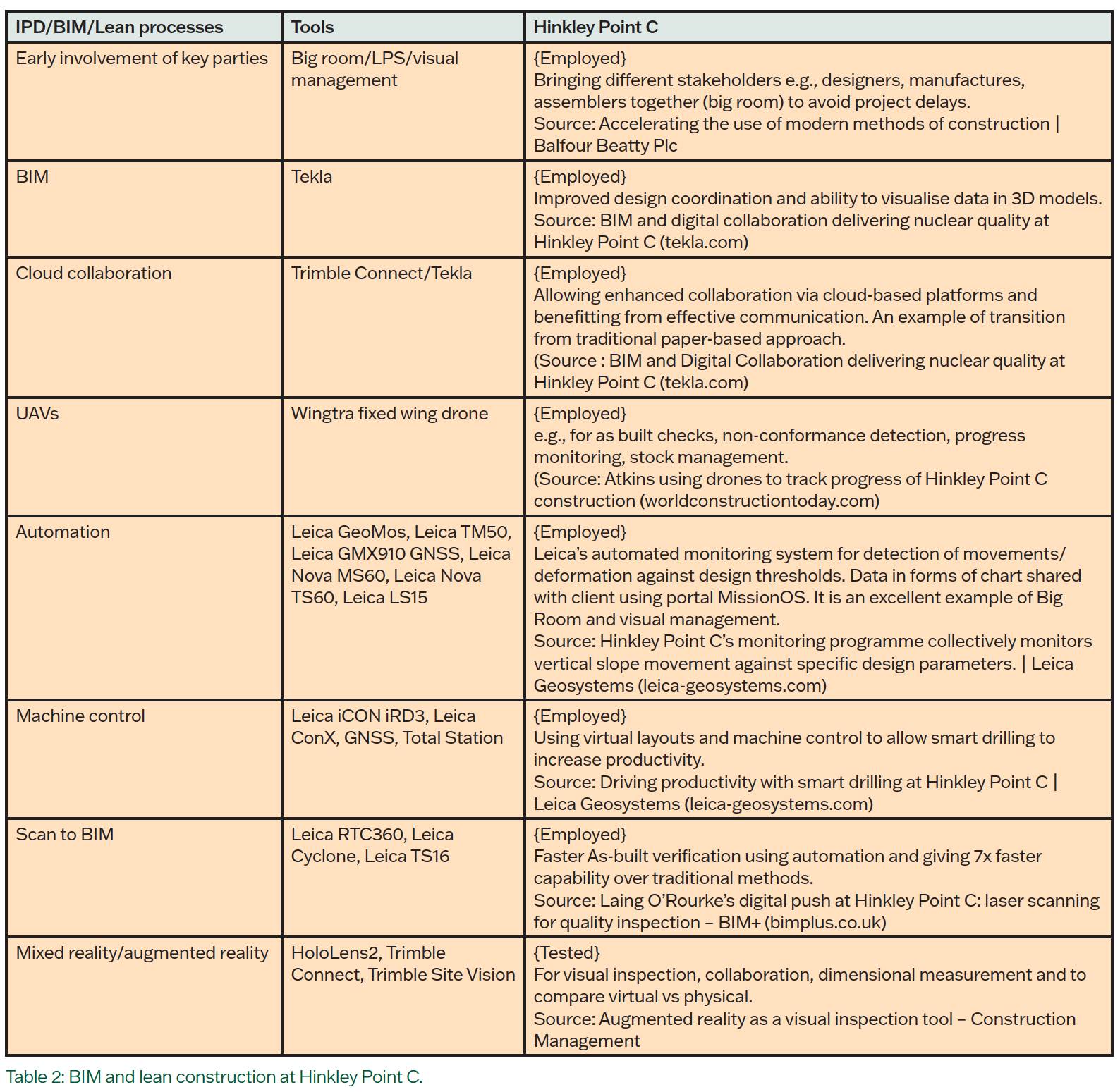

However, Suffer Health faced some challenges due to interoperability and model size. Table 1 gives extra information on some of these issues. Whilst Suffer Health demonstrated how the adoption of BIM and technology led to no cost overruns; Hinkley Point C (HPC), an enormous project worth investment of around £19.6bn (Rodgers, 2019), has shown a similar approach by adopting the most emerging technologies. Table 2 shows how HPC has employed and tested BIM and lean processes to increase productivity. Whilst Suffer has demonstrated the successful implementation of IPD, its benefits in terms of time and cost for HPC are yet to be fully evaluated.

Dave, B., Koskela, L., Kiviniemi, A., Tzortzopoulos Fazenda, P., & Owen, R. (2013). Implementing lean in construction: Lean construction and BIM. 71034.pdf (qut.edu.au)

Eastman, C., Teicholz, P., Sacks, R., & Liston, K. (2011). BIM Handbook: A Guide to Building Information Modeling for Owners, Managers, Designers, Engineers and Contractors (2nd ed.). John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated.

Fischer, M. (2017). Integrating project delivery. Wiley.

Hardin, B. (2015). BIM and construction management proven tools, methods, and workflows (2nd ed. Sybex.

Lichtig, W.A. (2005). Suffer Health: Developing a Contracting Model to Support Lean Project Delivery. Lean Construction Journal, 2(1), 105-112.

Oakland, J. S., & Marosszeky, M. (2017). Understanding lean construction. In Total Construction Management (1st ed., Vol. 1, pp. 2–21).

Routledge. https:// doi.org/10.4324/9781315694351-1 Sacks, R. (2017). Building Lean, Building BIM: Improving Construction the Tidhar Way (1st ed., Vol. 1).. Routledge.