A greying fellow reflects on...

Improving construction productivity

Part 5: Materials and productivity

IMPROVING productivity is not just about people and equipment; more effective use of materials contributes too. And it is fundamental to carbon reduction and increased sustainability.

Only future cost can be controlled. The amount of materials wastage is largely determined in advance by design and working methods, work organisation, ordering and delivery regimes. Retrospective records only confirm if material has been wasted, and where.

But a review of actual costs can point to where savings could have been made to help us improve in future. Keep cost coding and recording systems simple so that they can be consistently and accurately maintained by busy people.

Think about what information you want in the reports to help manage improving material productivity. I once received plaudits from an auditor for not routinely carrying out checks on the 80% of items that only made 20% of the cost; I just checked that their total was not significantly greater or less than expected, in which case the reasons would be investigated. The checks on the other 20% of items were rigorous and geared to helping reduce wastage.

Waste can only be reduced by the actions of those actually using the materials. Subcontract conditions should be framed with this in mind.

As well as requiring records necessary to demonstrate sustainability and carbon reduction, have a requirement for looking for more effective use of materials and reporting on the achievement.

Have conditions that incentivise avoidance of waste of materials provided to the subcontractor. But take care that the drafting precludes disputes that avoidable wastage has occurred.

Here are some points from a talk I gave some time ago on practical tips for reducing wastage:

- Find which 20% of the materials constitute 80% of the work. This is where the majority of improvement will come from. On a civil engineering contract these may be excavation and filling, concrete, formwork, reinforcement, pipework, instrumentation and controls.

- For the materials selected, assess what productivity/ wastage is achievable and monitor the actual. Spend some time on a regular basis considering what can be done to improve productivity.

- Define wastage to get clarity and give focus to minimising it;

- Gross wastage – the difference between quantity purchased and paid for and net quantity required for the finished work.

- Unavoidable waste – the amount of a material which has to be provided but will not form the net quantity of finished work.

- Avoidable waste – any other amount of waste. This will include material which is paid for but never used.

- Consequential waste – the ancillary cost of dealing with avoidable waste.

The talk went on to give examples of waste for concrete, formwork, reinforcement, granular fills and flexible surfacing, pipework and fittings.

The types of materials we use in construction will change and with them the particular areas of wastage. But the approaches that enabled effective use in the mechanical age will still be valid in the digital age.

Change and productivity

Managing change has always been a significant part of my career, and has probably changed more than any other aspect. Initially it was to ascertain the appropriate quantity and prices for the work that had changed in the best interests of the contractor I worked for, calculating and negotiating this largely retrospectively. Latterly it was to manage the quality, timing and cost of change in the best interest of both parties, and to predict the outcome in advance. Managing change is now more closely linked with productivity.

Change is common on civil engineering projects and is often seen to be a problem to be avoided where possible. Yet without change we will never get improved productivity; repeatedly doing the same thing repeatedly gets the same results. We should look and cater for change that will improve productivity and seek to minimise the adverse effect on productivity of unwanted change.

Looked for change can be catered for by a culture of innovation, already referred to. The process may start with the project risk register identifying upside risks or opportunities and managing them in the same way as downside risks, identifying realisation methods (equivalent to mitigation) and intervention dates (the stage in the programme where they will have to have been developed if they are to be implemented).

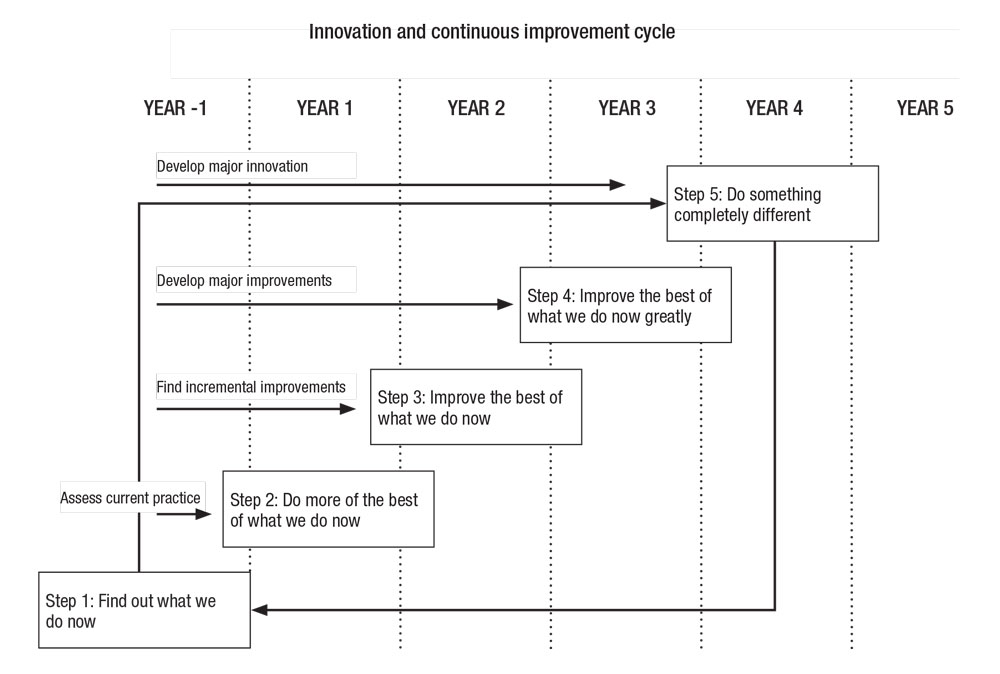

A five-step innovation and continuous improvement cycle planned for a water framework is appropriate for many long-term projects. All steps commence at the start of the project, but take progressively longer before implementation, reflecting the longer time required to realise each step.

- Step 1: Find out what we do now.

- Step 2: Do more of the best of what we do now.

- Step 3: Improve the best of what we do now.

- Step 4: Improve the best of what we do now greatly.

- Step 5: Do something completely different.

When Step 5 is being implemented start the whole process again. In this way continuous improvement in productivity should be achievable. The whole team including subcontractors and suppliers should be involved in the process. This may require some contractual incentive. On New Engineering Contract (NEC) contracts this is easily achieved by the assessment of compensation events for such changes not reducing the target cost. Whereas looked-for change will result in improved productivity, unwanted change will mostly have an adverse effect on productivity that can be minimised with good management.

CONCRETE

Unavoidable waste: The amount required for testing, that left in the skip or pump lines, the allowances for batching and positional tolerances. A small amount of surplus concrete is much less costly than having a small shortfall for a concrete pour. But note that the unavoidable waste is partially offset by the volume of concrete displaced by reinforcement. For a moderately (120kg/m3 ) reinforced structure this is 1.5% of the concrete by volume.

Avoidable waste: This can be from poor ordering, whether too much leading to surplus that has to be disposed of or too little leading to labour and equipment standing or even rework; inaccurate formwork, which is almost always oversized; poor workmanship, such as inadequate vibration, that results in rework; handling waste, as every time you move concrete a small amount is left on the ground.

Another avoidable waste: Fraudulent practice, such as the driver getting two delivery notes signed or not discharging the full load. When your neighbour gets a hugely discounted price for concrete for his driveway, it is not the concrete company or delivery driver who is paying for the discount. Consequential cost: Concrete that is not used has to be disposed of using resources that are avoidable wastage in themselves.

FORMWORK

Waste is not obvious, but that does not mean it is neither real nor large. Using the area of the concrete face requiring support allows us to consider unavoidable waste. This is necessarily a significant amount; there has to be overhang for kickers, vertical joints, fixing level laths.

Wastage can be reduced by designing component sizes to suit formwork modules. For example, a wall height of 4.60m gives a high proportion of filled formwork face from two sheets of plywood 4.86m high allowing for 100mm kicker and 100mm freeboard; a base thickness of 500mm is good for a form from half a sheet of plywood 0.61m high to allow for positional tolerance of blinding and top freeboard.

Wastage can be reduced by designing for repetitive use.

REINFORCEMENT

Wastage is not common, but can be from late revisions to bending schedules, badly stored bars becoming lost or damaged, bars on delivery note but not on the lorry, overcharge by the supplier. Simple management processes will prevent these. Does the tare weight of the lorry match the total on the bar schedules? If not does the number of bundles match?

The lack of wastage can be easily monitored by the ratio of reinforcement cost to concrete cost. I once found that the supplier had submitted incorrect invoices by noticing that the ratio of reinforcement to concrete cost was hugely wrong. Accountants checks of invoices against delivery notes had not picked it up.

GRANULAR FILLS AND FLEXIBLE SURFACING

Do setting out to achieve a positive deviation within tolerance from nominal position except on top layer. Positional tolerances of the top of each layer decrease with every layer from capping up. Saving on the expensive wearing course relies on the formation level for capping being art the high end of its tolerance.

Work out what tolerance is achievable: accuracy of instruments, accuracy of user, particle size of material all have an effect.

Make sure material is optimum moisture content.

Minimise rehandling, deliver to point of use where possible.

PIPEWORK AND FITTINGS

Prevent wastage by checking that orders conform with design and deliveries conform with order and quality, then prevent damage during storage, distribution and installation. Change is common on civil engineering projects and often seen to be a problem to be avoided where possible.

Contract conditions should facilitate efficient management of change. Generally, the fewer amendments to standard conditions there are the easier administration is and the less is scope for misinterpretation. Use of software packages such as CEMAR help efficient administration of change in accordance with the contract. If you don’t use such a software package for whatever reason, follow its processes manually. Conforming with contract tends to be more effective in the long run.

Disputes, whether informal or formal, are to be avoided or at least minimised; 100% of dispute resolution costs are a drain on productivity. Efficiently kept records help in this regard. ‘Records, records, records’ is a mantra often cited in advice on contractual change management. But one set of records sufficiently comprehensive and accurate for matters of fact and quantum to be readily agreed is more effective both in compilation and use. I once worked on a claim for delay and disruption caused by change on a railway station reconstruction where several section engineers and foremen each kept a daily diary, with some overlap of the activities covered. They were in a standard format, but the content varied from longwinded essays to terse comments. They also gave different versions of the same events.

Finding all of the facts required was difficult until I discovered the client’s supervising engineer kept a daily diary that was comprehensive yet simple and clear. For each work gang he listed whether the activity was started, continued or completed on that day and whether the gang resources differed from the previous day. He might add a bullet point reference to any unusual event that affected the activity. Producing a resourced as-constructed programme that all parties readily agreed to was straightforward using his diaries. And I doubt if it took him more trouble to compile than the less useful diaries of the section engineers.

Another site manager I worked with whose weekly diary reports were a joy to use provided an A4 photograph of the site fed into his computer and then annotated it with the relevant information one would want, sometimes with an inset photograph illustrating an important point. Pictures may paint a thousand words, as the cliché says, but they may not always paint the words that you want to see. I once encountered a defence against a claim for exceptionally wet weather that purported to show that the claimant was not delayed by rain but by his dilatory progress on reinforcement fixing. The photograph showed partially erected reinforcement for a bridge abutment surrounded by a lake of floodwater.

A larger occasion of photographs being used to counter a claim I was involved with occurred many years earlier on a motorway contract. There was a large claim for rock unexpectedly encountered in drainage, and in assessing the quantum, every time the resident engineer came across an item for JCB3C he crossed it out. When this was challenged, he took us to the library of hundreds of monthly progress photographs. Photograph after photograph for month after month had excavators and dozers visibly working, except for JCB3Cs which were always posing doing nothing as if in a brochure.

Now that the digital age makes written and photographic records so much easier to create, we should use them thoughtfully. Now that the digital age makes written and photographic records so much easier to create, we should use them thoughtfully. It is easy now to take huge numbers of photographs and then time consuming to find the ones that we want, if they are there at all. Limit the photographs that you create, perhaps a couple from fixed locations at fixed intervals to show the rate of progress and then suitably dated and annotated photographs of particular events. Similarly with written and numerical data, select it so that it shows what you want to communicate and does not get lost in a sea of data. Programme charts illustrate this point well. Just as with pictorial art where people do not look at and buy ugly paintings, people don’t look at and buy into ugly programme charts. Ensure that the presentation is in a form that the people who can improve productivity by using them will actually use them.

Improving your own productivity

Improving you own productivity will have a positive impact on the overall productivity of the industry, albeit in a small, hard to measure way. It should lead to the rewards being shared, through your employer’s business being more successful and your salary being bigger. It could be argued that you only improve industry productivity if you become more effective than your fellow professionals who retire; the rest of your improvement is just becoming a better surveyor. The route to both is CPD. If carried out effectively it will improve your productivity throughout your career. The way you conduct your CPD can itself be made more productive.

Firstly, plan your CPD so that it will result in you fairly immediately improving productivity. Your CPD plan should include items which broaden your horizons and give you an understanding of emerging techniques not yet connected to your job and items that will help you towards your next career step. But the majority of your plan should be for items that will help you to be more productive in your current role. You don’t become more productive by being able to do things that are not required.

Secondly, put the emphasis on activities that will improve your strengths. The Corporate Leadership Council’s Managing for High Performance and Retention research found that emphasis in performance reviews on performance strengths resulted in +36% change in performance, suggestions for doing the job better, skills needed in the future and long-term career prospects +7%, +5% and +4% respectively, whereas emphasis on weaknesses had a negative impact on performance of -26%. Training on your weaknesses may just result in you having a better set of weaknesses. Remember the theory that if you spend enough time doing things well you won’t have the time left over to do things badly.

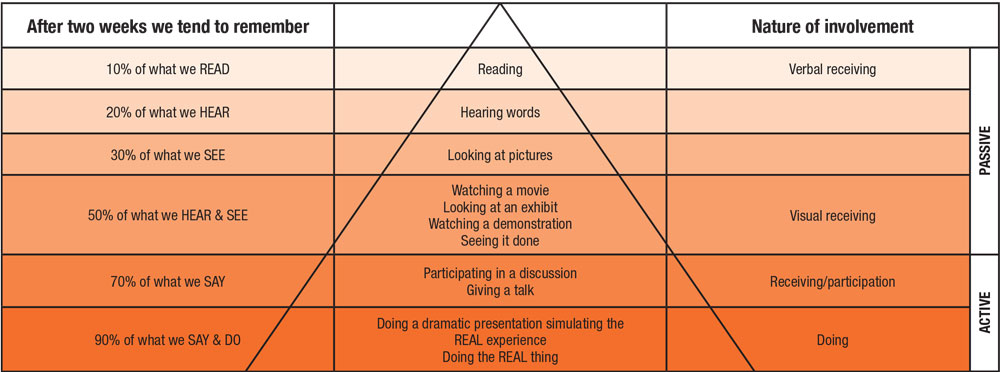

Thirdly, ensure that more of your CPD activity is in a format that results in a higher retention of the learning as illustrated by the Cone of Learning by Edgar Dale

If the learning activity itself doesn’t include ‘doing’ or lead quickly to it by practice at work, find some way of ‘doing’ for yourself. After a CPD activity, I sometimes created a single page of learning points from the course, such as the illustration of the Principles of Lean Construction in an earlier reflection. CICES CPD policy uses the plan-learn-reflect model. As part of your reflection, consider how the activity has contributed to your improved productivity. This reflection will help you to plan more productive CPD in the future.

In summary

I can relate so much of my career to seeking improved productivity that I could reflect on even more, but I think these reflections have illustrated all of the points I want to make. Any more would just be an unproductive grey fellow boring on. Among the points made have been:

- We seek improved productivity throughout the construction industry, at corporate, project and individual level.

- We can all contribute to improving productivity. Systems for instigating and implementing improved productivity need to be accessible and used by everyone in the team. For success, a culture of improving productivity needs to be adopted throughout the team.

- Modern technology should make it easier to take steps that improve productivity. Use it so that data gets to the people who can make it happen, make sure the data doesn’t get lost in a silo that only the technologically advanced can access.

- Improved productivity doesn’t happen much by accident. Deliberately seek it.

- Be a magpie. Learn from what others have done. Use history to adapt for the future.

- Improving productivity always needs change. Doing the same again will never achieve it.

Cone of learning (Edgar Dale)

A key part to improving productivity is to measure it, and present the measurements in a suitable form for appropriate action. Throughout the broad range of civil engineering surveying and the enormous changes in the past decades and yet to come, measuring things and analysing, commenting on and communicating what we have measured is always a large part of what we do. We are well placed to effect improvements in construction productivity.

If most of us spend some of our time seeking improved productivity, we will make it happen. I hope that these reflections will encourage you to do just that.

George Bothamley FCInstCES