Lessons from rail

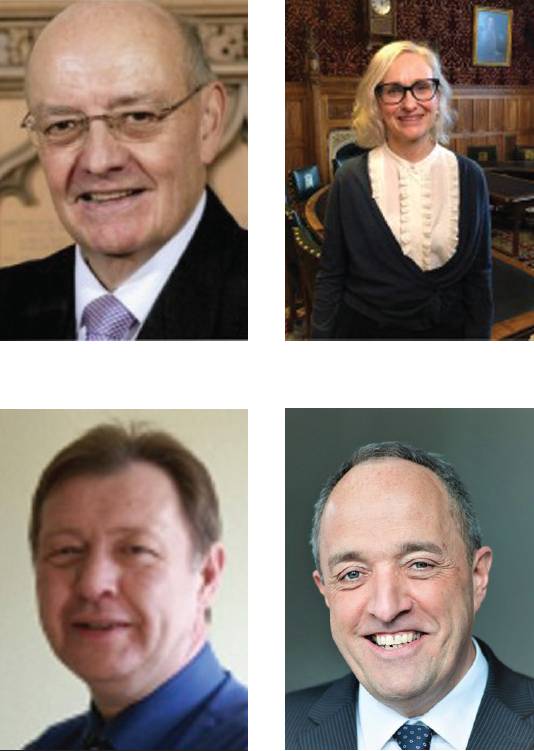

Peter Hansford CBE with Isabel Coman CEng FICE, Managing Director, In-house Services and Estates at the House of Commons, John Riches FCInstCES, Managing Director, Henry Cooper Consultants and Paul Pethica FCInstCES, Principal, Morsson Pyper

ONE of the panel discussions from this year’s CICES Commercial Management Conference looked at lessons learned in rail. The panel discussion looked at lessons within and outside of the sector, and within and outside of the UK. The panel was chaired by former government construction adviser Peter Hansford CBE, and comprised: Isabel Coman CEng FICE, managing director of in-house services and estates at the House of Commons (formerly SCS); John Riches FCInstCES, managing director of Henry Cooper Consultants; and Paul Pethica FCInstCES, principal of Morsson Pyper.

Peter Hansford: Back in 2016, I was asked to review contestability in the UK rail market, looking at Network Rail’s perceived monopoly position and the extent to which it was discouraging third parties from investing in enhancement projects and how that was affecting costs. That review, ‘Unlocking rail investment: Building confidence, reducing costs’, found that there were many – too many – barriers, both real and perceived, by third parties when it came to working with Network Rail. It wasn’t easy to deal with. Its standards, procedures and asset protection processes were inappropriate. It was resistant to change. Not surprisingly, this put off funders as investment costs were much higher than needed and innovative contracting was blocked.

In response to the review, in 2017 Network Rail published its Open for Business Strategy. So, four years on, has private funding increased? Have costs reduced? Is Network Rail truly open?

Isabel Coman: I spent 20 years working on major rail projects, from HS1 to Crossrail to HS2, with London Underground and Transport for London in between. What was common on every project were two things:

- Change. On every project the client hopes the contract covers everything and that there will be no change. Yet on every project, no one can foresee specific challenges. Every project doubled or tripled its original contract value – that was my reality.

- Talent, resources and skills. Challenges, whether technical or commercial, were overcome eventually by the incredible people working in the rail industry.

Rail is unpredictable. Yet we assume it will be predictable. How do we make contracts recognise that change is a large proportion of what we do? How do we simplify dealing with the complexity of future unknowns? How do we reflect that critical decisions will be made during the lifetime of a project and not just at the outset? How do we recognise compounding change? One single big change is relatively simple, but hundreds or thousands of changes that compound day after day are almost impossible to manage and become all-consuming.

We need contracts that are able to free-up skills to focus on delivery and to drive efficiencies, rather than on the mechanisms that protect your party.

John Riches: We have to focus on cost instead of spending money on the wrong things. The investment that is currently in bureaucracy has to go into design and management. If you look at the A14 road upgrade, that project excelled from the crisis of having Carillion – one of the four original contractors – going bust. That led to the contract being torn up and rethought. How can we learn from that in rail?

On every project the client hopes the contract covers everything and that there will be no change. Yet on every project, no one can foresee specific challenges. Every project doubled or tripled its original contract value – that was my reality.All the developments we are seeing now in the Construction Playbook and Network Rail’s CP7, no one knows how well they will work. Politically our projects are appraised on what we have to spend rather than what they will cost. We have a legal definition of what disallowed costs are, yet it is of no use when the nuts-and-bolts reality is that we don’t focus on cost.

If we want the infrastructure industry to stop making people go bust, we have to stop using devices like disallowed costs. We have to stop saying you can’t have a compensation event because you didn’t fill in a form yesterday. We have to stop rowing about change before we have determined if it is a change. If you want collaboration, you won’t get it by nicking someone’s money. We have to find another system. We need to get out of the straitjacket we are in.

Whatever we come up with and however we dress it up, we have to get beyond the traditional thinking that we must have a price of some sort – this is not looking at costs, it’s looking at outcome. Concentrate on encouraging the right skills so we get the right people. If we stop making the industry so unattractive and full of punch-ups, more good people will come into it.

Isabel Coman: We have to incentivise transparency of cost. We have to incentivise being clever. People shouldn’t feel pressured to come up with the answer that is expected of them and put unrealistic schedules on the table because there is a penalty against them not doing that.

Paul Pethica: If we look at benchmarking as a potential solution, we need to look at other territories and ask why are their costs so much less?

We have to stop saying you can’t have a compensation event because you didn’t fill in a form yesterday. We have to stop rowing about change before we have determined if it is a change. If you want collaboration, you won’t get it by nicking someone’s money.You can say it is because of the extra hoops we have to jump through around planning, health and safety and contracts, but we know all about these. Many of our neighbours have hoops to jump through too. We can learn lessons from our neighbours – near and far, good and bad. But we need to get our own benchmarks in order before we compare ourselves with projects and major capital works programmes overseas.

Isabel Coman: Benchmarking is important, but we don’t do it well enough. It’s too simplistic. We need to understand the specific context of everything we deliver to be able to get really good benchmarking data so we can compare it to the actual situations we find ourselves in. It isn’t easy. While we have rail measurement, there isn’t a true industry standard that says you have a million planning applications and X amount of change – we can’t benchmark against Europe without those specifics.

Paul Pethica: When working with the big UK client organisations, you have a large pool to swim through before you reach the shore and can deliver innovation. It’s time-consuming to do, and often clients miss out on the excellent innovations that can be initiated and provided by their supply chains.

We need to release potential. Why do we spend more per track mile in the UK than Europe? National Highways [formerly Highways England] and its UK counterparts are amongst the best organised and informed of the highway delivery organisations in Europe, and can clearly demonstrate value for money, yet we don’t have that equivalent standing in rail. Innovation is discouraged and clients may not be aiming for that, but that is what the result is.

Peter Hansford: Lessons in rail fall around three themes:

- Innovation

- Complexity

- Collaboration

Throughout these, what is clear is that rail is a people business. It’s all about finding and encouraging and promoting good people to ensure we get the outcomes we need.

Peter Hansford CBE, Isabel Coman CEng FICE, Managing Director, In-house Services and Estates at the House of Commons (formerly SCS); John Riches FCInstCES, Managing Director, Henry Cooper Consultants; and Paul Pethica FCInstCES, Principal, Morsson Pyper were speaking at the CICES Commercial Management Conference, London 7 October 2021