Greying Fellow

A greying fellow reflects on...

Improving construction productivity

Part 2: How we can all contribute to improved construction productivity

I WAS involved with, or encountered, activities that promoted increased productivity and effectiveness from an early stage of my career, but it was only in the final third when I worked on water industry capital infrastructure programmes that contractual obligations made it a core part of my work. So, I will start by looking at some things we did to improve productivity on the first such framework I was involved with.

The framework was for option selection, design, construction, maintenance, and hand back of about 600 new and refurbished wastewater assets of individual value up to £2m. Its commercial model was a target cost contract taking into account whole life costs, with the target derived from historic average cost for similar assets with an uplift for inflation and reduction of an efficiency factor.

Further increased efficiency was incentivised by a pain/gain share provision for cost variance from the target. I was lead commercial surveyor for about 60 of the individual projects.

Generally, large efficiency gains were made from improvements in option selection and design and procurement processes through business as usual for the contract partner being more efficient than the previous in-house client processes. Since the targets were based on average historic costs, some projects were costing more than target but these were more than offset by those costing less than target.

My portfolio of projects included eight for first-time sewerage in very small villages which had untreated discharges to inland water outfalls (IWO). These were all costing hugely more than the targets, but were acceptable on the ‘swings and roundabouts’ principle that they were more than offset by projects having costs less than target. That is, until the client introduced an extra 32 IWO schemes to meet a revised statutory obligation. We needed to find a radical improvement in productivity on these schemes.

Projects had hitherto been allocated to delivery teams on the ‘first taxi on the rank’ system, whereby the new project went to the least busy team. The original IWO schemes had been scattered amongst four teams, so the first change was allocation of all IWO schemes to the team who already had most of them.

Swarm

The project director gave the team leader the goal of making IWO schemes pain/gain neutral, a huge turnaround. This was an example of swarm theory in practice. A couple of years later the client sent about 70 of the framework team on a half-day course on swarm theory. This used the analogy of bees finding their own way to a pollen source if an obstruction was put in place.

Some took a while to find their way round the obstruction and some took convoluted routes, but all found their way and most of them quickly by the best route. The message was that senior managers should not be too prescriptive in their directions. If they instruct actions for activities that they can’t know enough detail about, the action will not be the best and they will also inhibit people from thinking for themselves.

Both these result in reduced productivity. Instead, they should set goals and leave the team members to score them. The framework project director knew this without needing a course.

The now single team for all IWO schemes was able to initiate a number of processes that together dramatically improved productivity including:

- Teamwork: A dedicated team with regular meetings to focus on all aspects – design, construction, commercial – to become fully aware of each other’s needs and contributions.

- Continuous improvement: A culture of continuous improvement was created, having the confidence that although what we had previously done was good, it could probably be improved upon. How and why things were done was questioned. Costs of alternative solutions and methods were rigorously compared – the least cost is not always obvious.

- Standardisation: We recognised that although all civil engineering projects are different, they all also have similarities. A standard scheme layout was devised that could accommodate any orientation of inflow, outflow and access by flipping left or right, up or down. The key components such as biological filter units, pumps, screens, control panels were standardised in a small range of sizes to give extensive repeatability. This was key in enabling cost benefits in design, supply chain management, component cost, programme flexibility, reduced construction time and reduced site management.

- Supply chain: Standard components and visible programmes enabled more term contracts to be set up including civil works and metalwork which had hitherto always been individually tendered.

- Visible and flexible programming: It was recognised that the key to achieving the required completion dates was to start construction on a site and start commissioning hand back for another site every three weeks. Which sites didn’t matter, just any one of each. The original programme clustered sites so that those with the same client operations staff or planning authority or other third party progressed sequentially. The team meetings focused on the progress of key issues such as land acquisition, availability of power and communication lines, planning permissions. If difficulties were slowing progress on one site, another would leap frog it on the programme to maintain the rate of construction starts.

- Risk management: Risk schedules were established at feasibility stage, included mitigations and intervention dates and were frequently reviewed. Alternative costing of solutions included risks, leading to better decision making. Feedback of actual cost items was used to refine cost forecast and risk allowance for later schemes.

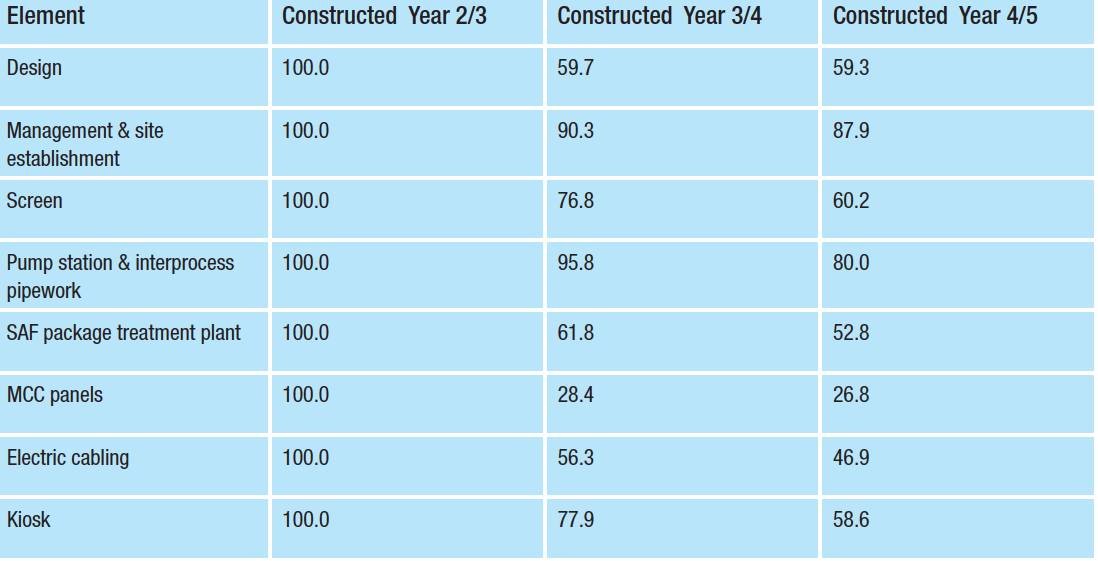

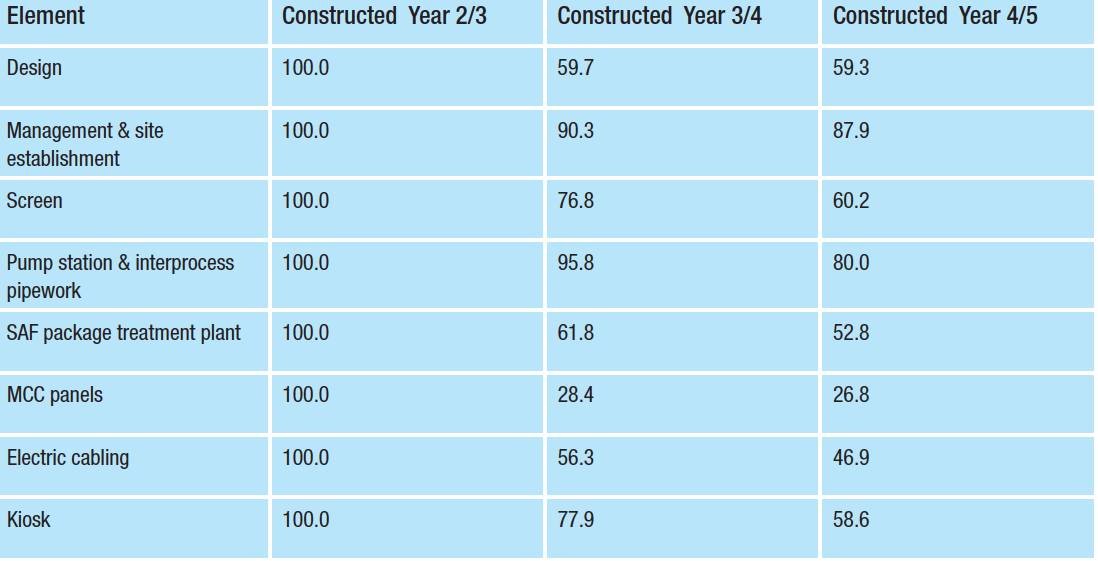

Table 1: Index of capex costs for various elements of IWOs constructed in Years 2/3, Years 3/4 and Years 4/5 (adjusted for price inflation).

The effectiveness of these working practices was demonstrated by comparative costs, shown in Table 1. All elements showed significant productivity gains, some quite dramatic. Efficiency savings were £7.6m on £30m expenditure.

Technical and digital developments in the years since this IWO programme make the path to improving productivity much different.

Data is more readily available and comprehensive and can be processed much more quickly. Communication of the output from the data is faster and can be visually attractive.

But the principles of what we did are still valid.

Adapting them to suit modern conditions should enable slicker improved productivity than we achieved.

Collect the data, analyse and use the relevant parts, communicate them throughout the team to the people who can use them to make the change needed, feedback how well it is working.

In the years following the IWO initiatives, team members continued to seek improved productivity on their new projects, looking forward for new needs and ideas and backwards for ideas to update and adapt.

Some of these will be illustrated in my next reflections.

George Bothamley FCInstCES