Technical Drawing

The importance of technical drawing

Author Chris Valkoinen on his new collection of technical drawings

TECHNICAL drawing is, in my opinion, the most underappreciated technology at the foundation of our modern world. Whether it is architectural, mechanical, civil, statistical or scientific, our ability as a species to record information in a visual art form is fundamental, both to who we are and our success.

Our earliest surviving maps are around three (or more) times older than the written word and include star maps in cave paintings and depictions of pre-historic landscapes etched into the bones and tusks of mammoths.

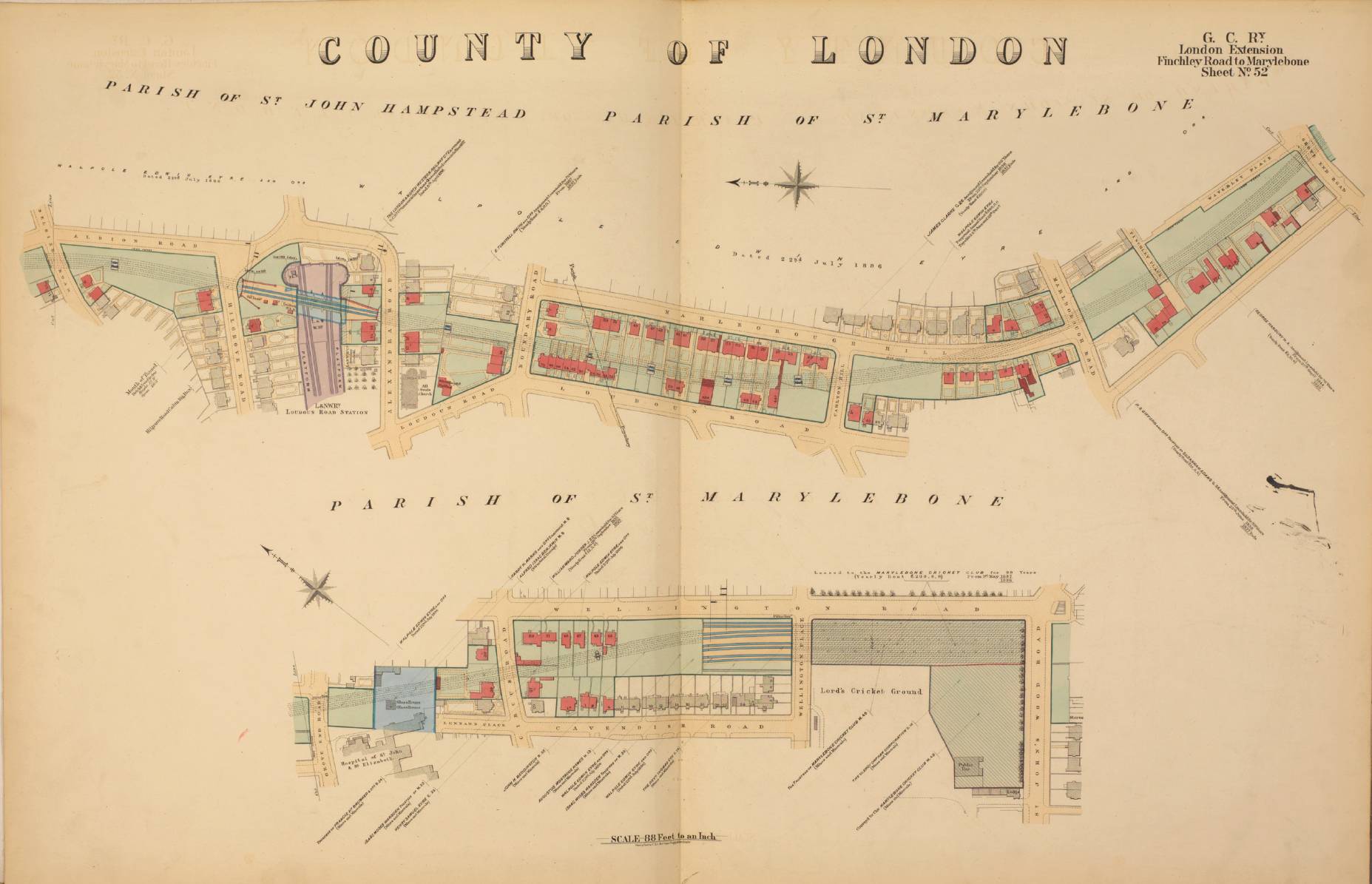

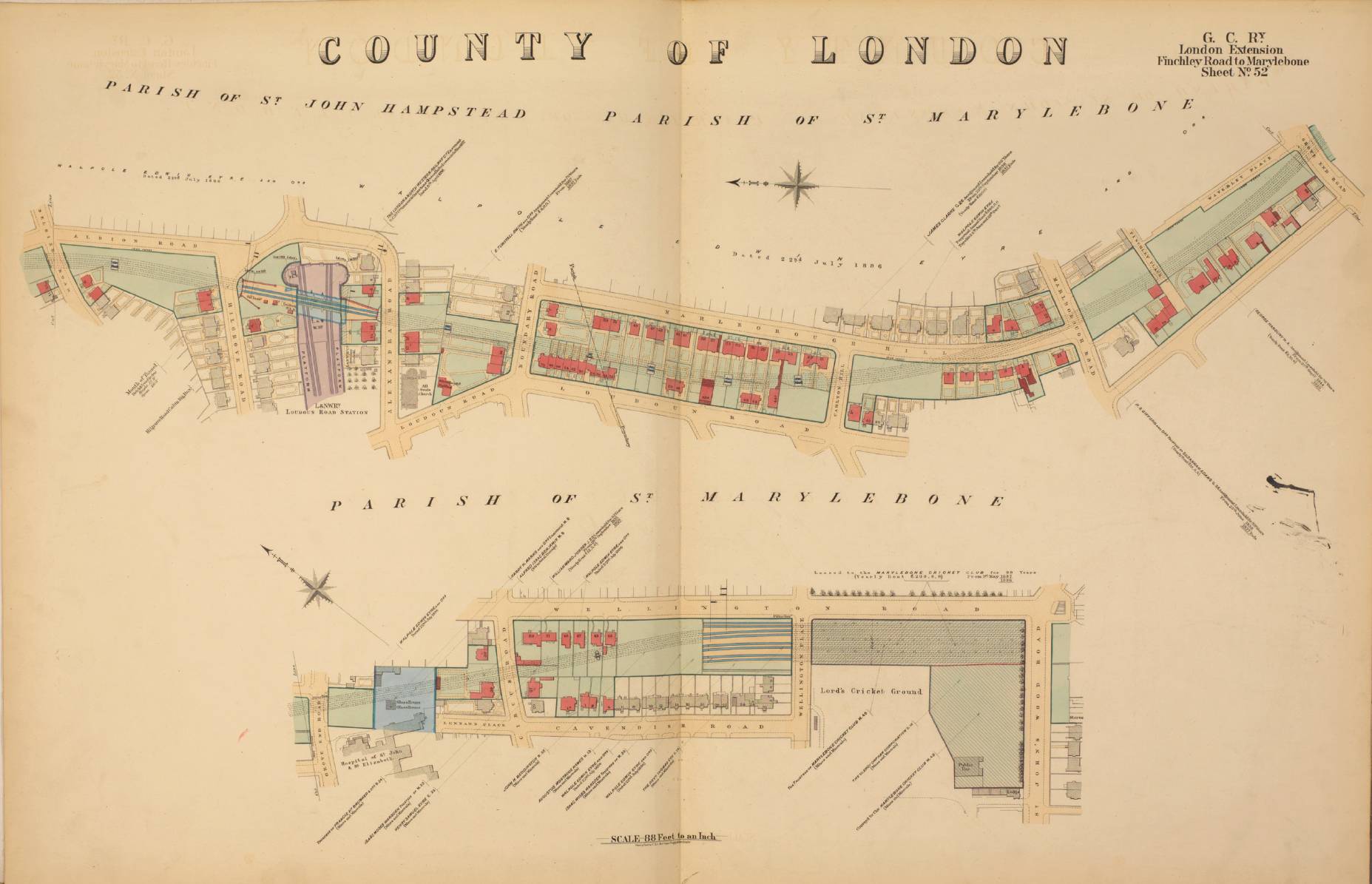

Volumes of beautifully coloured land plan books were produced to record the land owned, rented, and leased by the railway companies. This drawing shows the Great Central Railway’s tunnels on the approach to Marylebone station that opened in 1899. The railway passes underneath Lords Cricket Ground, for which owners Marylebone Cricket Club had a 99-year lease which only ended in 1999.

Our first evidence of architectural plans (on a statue of Prince Gudea of Lagash) are more than 4,000 years old. We know that Ancient Roman architects made extensive use of technical drawing in their designs, even if none of them survive today. More importantly, the industrial revolution on which our modern society is founded, could not have taken place were it not for the technical drawing skills of engineers and draughtsmen.

So what is it that makes technical drawings so important?

Essentially, they are a tool of communication, for ideas and information. Technical drawing enabled engineers to share their designs with others, thus allowing them to focus on their work so that the process of manufacturing and construction could be carried out by others.

Whilst it is not impossible to communicate designs in writing, the adage that ‘a picture may paint a thousand words’ applies nowhere more than in technical drawing. From the 1860s onwards, blueprinting techniques allowed for inexpensive copies of drawings to be made far more easily and shared between the various people responsible for making the designs a reality.

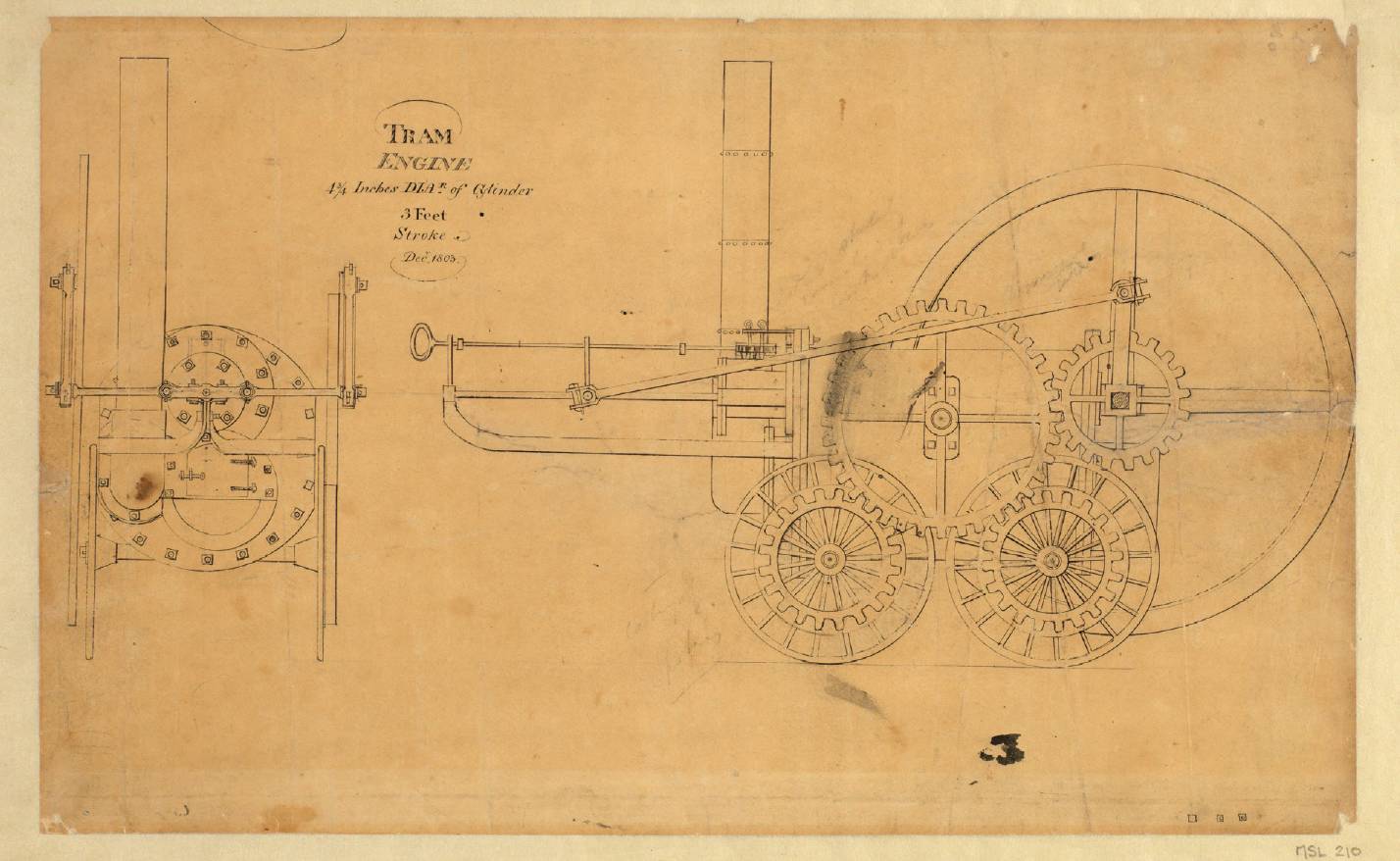

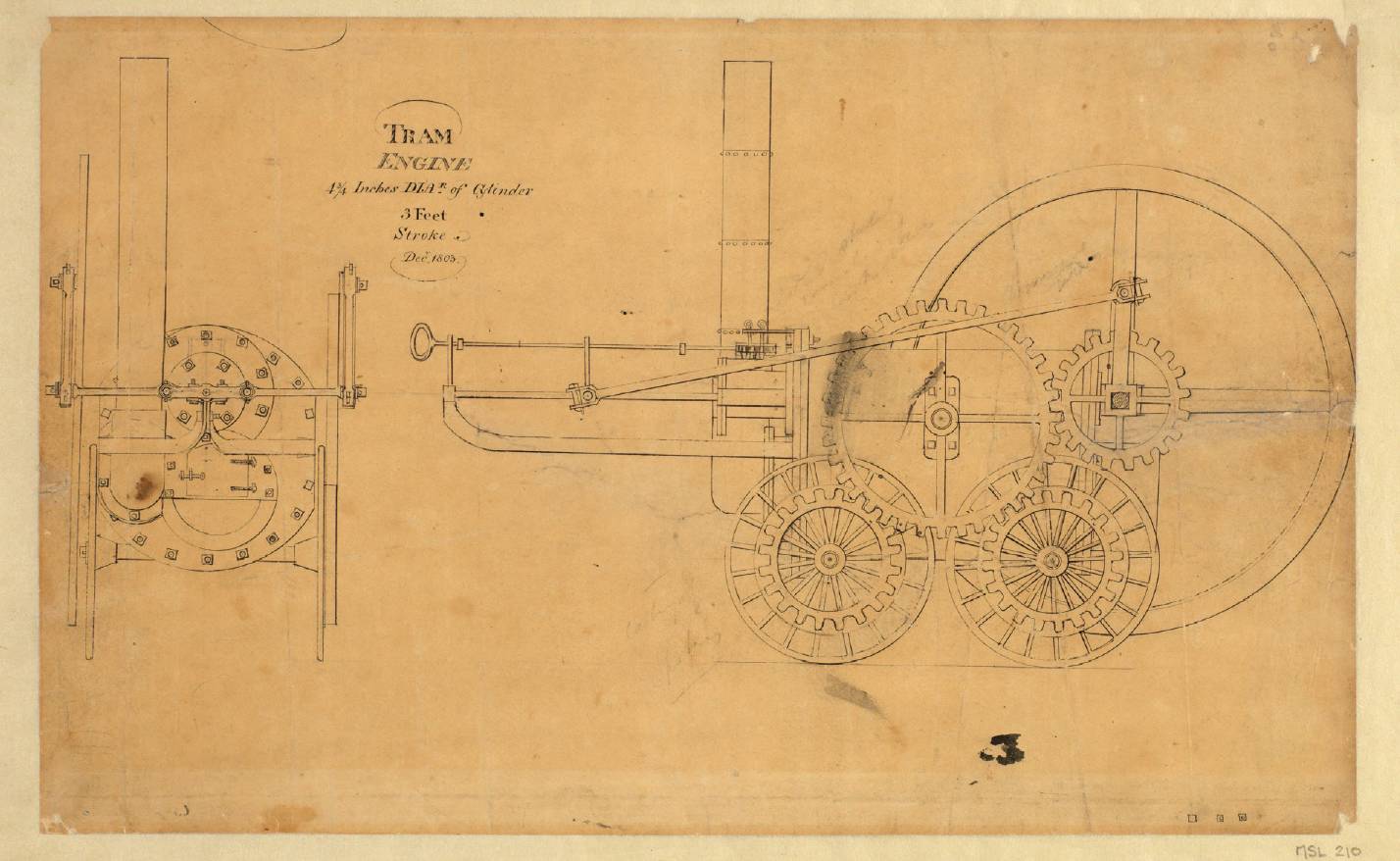

This is the world’s first drawing of a steam locomotive, but its design disagrees with what we know about Richard Trevithick’s Penydarren, which is credited as the world’s first steam locomotive. Despite significant research, the subject of the drawing remains a mystery. Could there have been another engine before Penydarren?

Additionally, technical drawings allow communication of ideas over distance. Engineers Boulton and Watt set up Britain’s first mechanical engineering drawing office partly because their huge atmospheric steam engines (the size of multi-storey buildings) could not be transported across any distance, so the drawings were sent to the site of manufacturing for the engines to be built locally.

For architects and surveyors, the ability to submit their drawings in front of governments was an important part of the process in gaining permission to carry out their projects.

Perhaps most crucially, technical drawings permitted communication of ideas over time. Engineers could record their designs and iterate upon them, sometimes using the drawings themselves to make adjustments as they mapped out the interaction between components on paper, a process that was otherwise achieved through costly physical models and prototypes.

Storing a record of the design enabled the repeated manufacturing of machines and their parts, thus facilitating economical repairs. A record of the design was also a prerequisite of the standardisation and mass production we are now so familiar with today.

Finally, technical drawing was an important part of the patent process, providing a record of the inventor’s ideas to protect them from theft and exploitation.

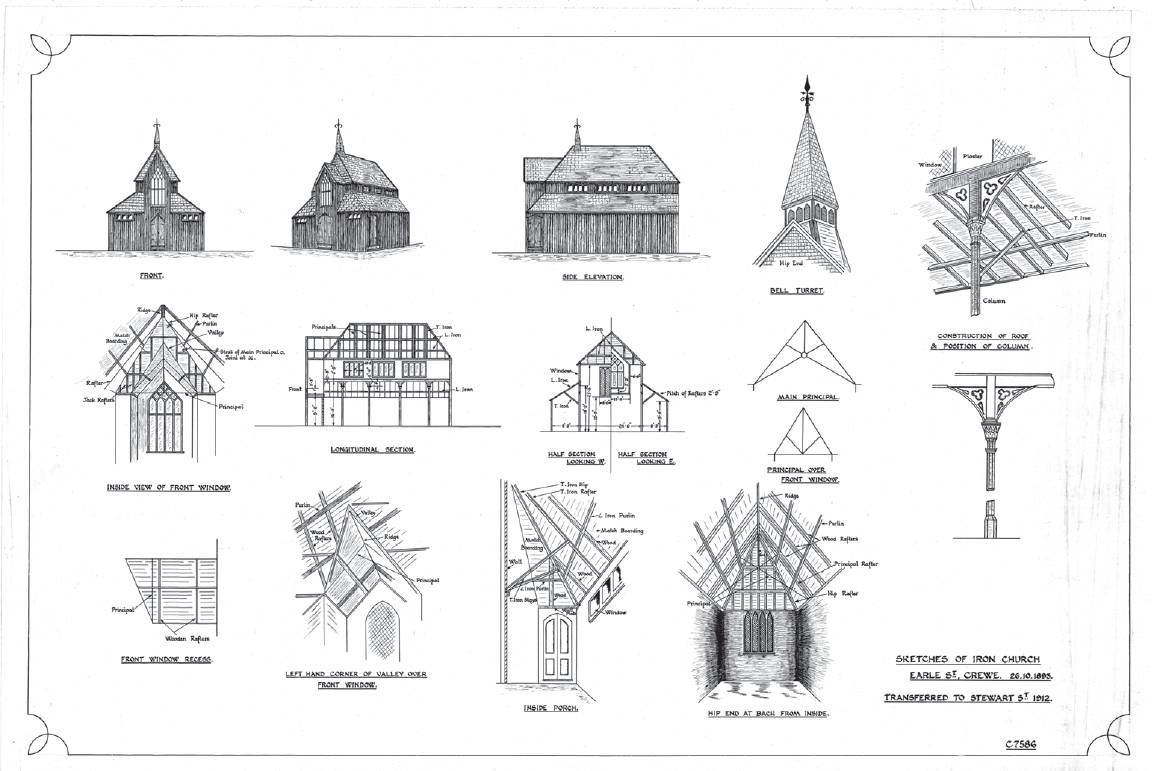

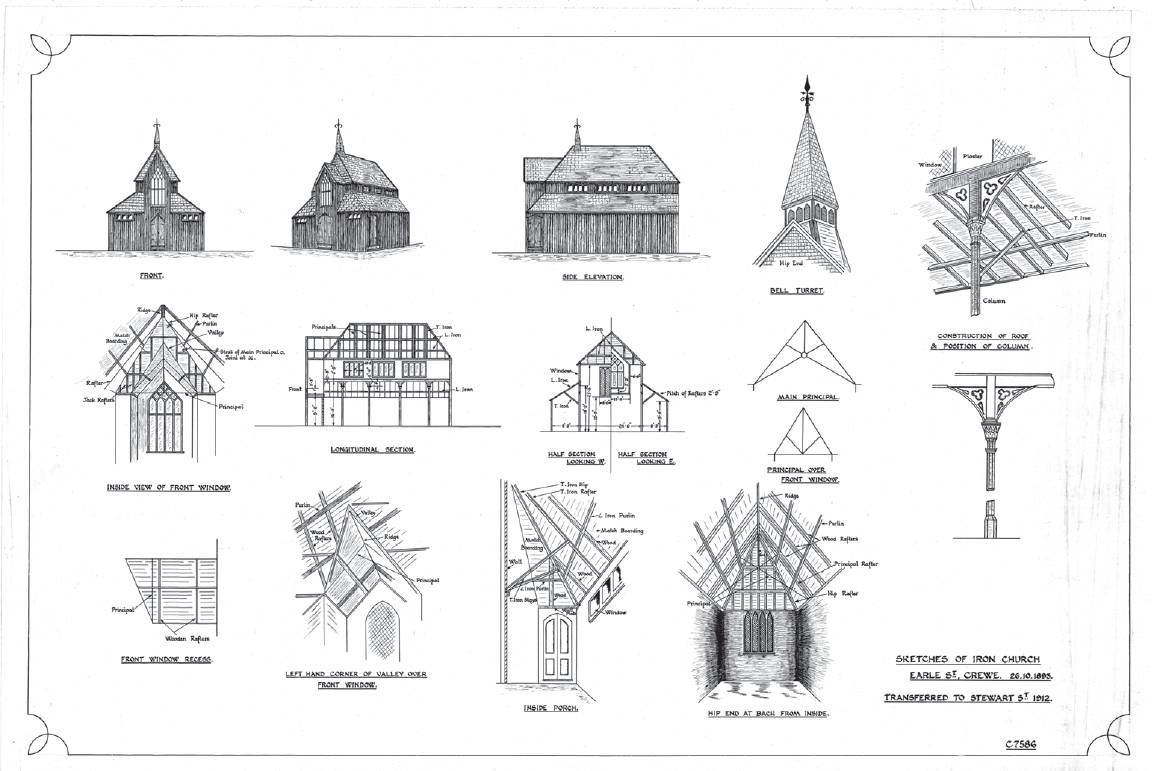

Drawings provide great insights for historians into the social impact of the railways. Large towns like Swindon and Crewe sprung up around the works that employed thousands of people to construct the railways’ locomotives, carriages, and wagons. To support those new settlements the railways built their own hospitals, schools, and churches like this drawing of St Peter’s church in Crewe. It was built from iron and was returned to owners British Railways when it was demolished in 1958.

The draughting skills of the engineers of the 19th century were crucial in unlocking the benefits of technical drawing. Without them, the advance of technology and the industrial revolution would have been a much slower affair.

Our world would look very different without it.

There is, however, one other thing that makes technical drawings important, but it is not something that likely sat in the minds of the people that created them, and that is their ability to be used to help us understand our history.

Throughout the last two centuries, almost everything around us that has not been created by nature has been subject to human design. Whether it is the products we buy, the machines we use, the buildings we live and work in, or the infrastructure that sustains and transports us, technical drawings will have been produced for it during the design process.

Sometimes those drawings were ephemeral and disposed of when they served no further purpose, but in many cases, they still survive to this day and are now a valuable record of our past.

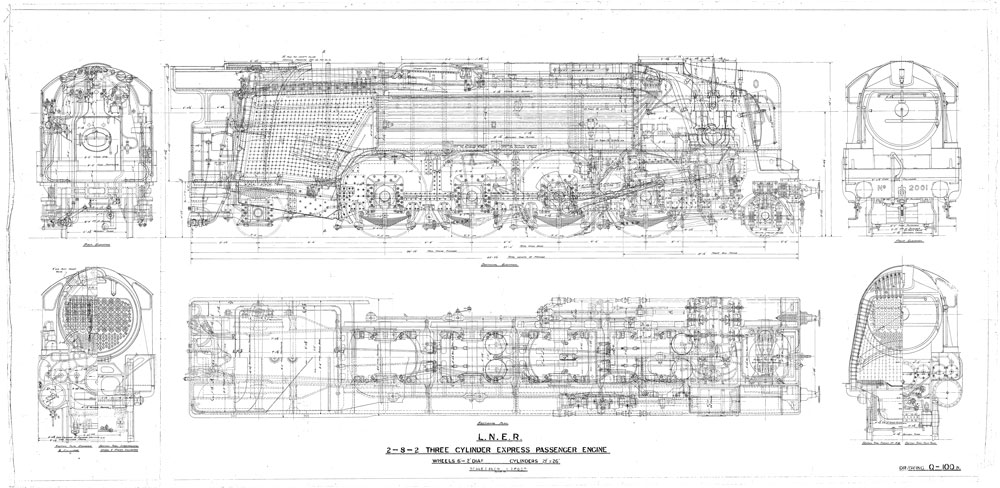

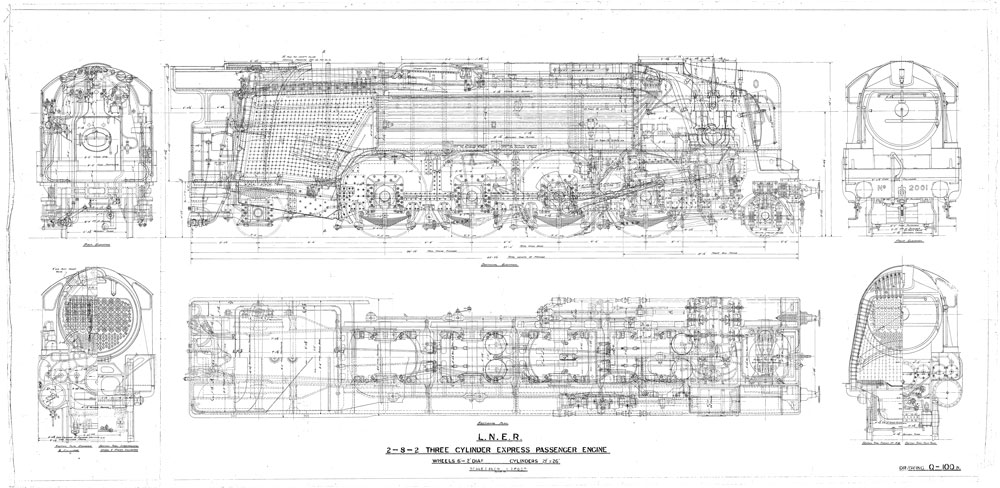

The team that built Tornado are repeating the endeavour by constructing a new locomotive to the design of the London and North Eastern Railway’s extinct P2 class. This is one of more than 400 drawings that were scanned from the National Railway Museum’s collections to support the project.

So what value are technical drawings to a historian?

Firstly, it is not uncommon that drawings outlive their subjects. Maps record infinite details about our changing historical landscapes and are invaluable in the understanding of the surroundings in which our recent ancestors lived. Our urban landscapes are forever changing, and from the humble terraced house to the great palaces of power and industry, architectural drawings can reveal the nature of long-demolished or modified buildings.

Drawings reveal not only the ‘what’ but also the ‘how’.

A photograph can show what a machine looked like but an engineering drawing shows all the intimate details of how it worked. It even allows that object to be recreated from scratch, and in doing so the skills needed to create and use that object can be relearnt.

One group of engineers at the A1 Steam Locomotive Trust put that idea to the test and built a new express steam locomotive using designs that are now over 70 years old and the result was Tornado, an engine that now runs at up to 90mph on the modern railway network.

Finally, historical drawings allow historians to understand the ‘why’. Why did engineers make certain choices about the designs they made?

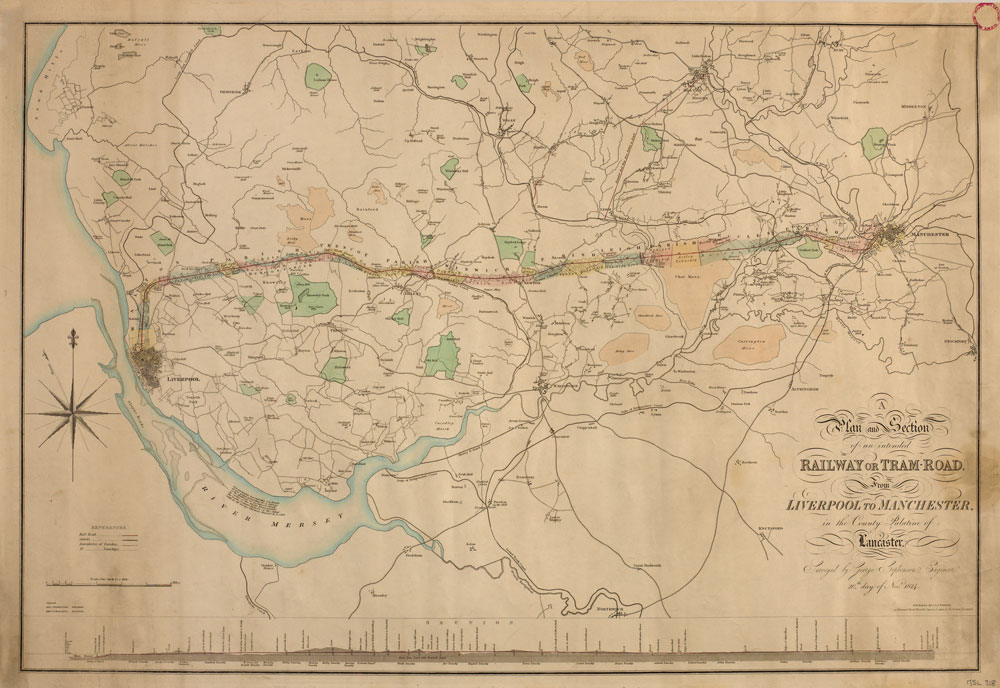

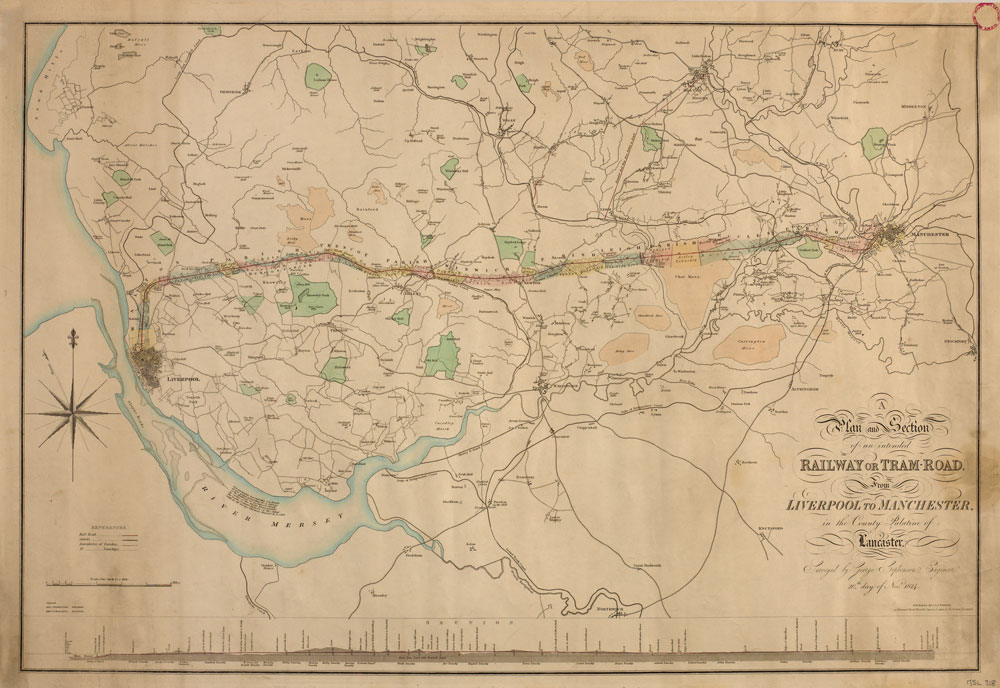

Early Victorian engineers were often generalists. George and Robert Stephenson could turn their hand to mechanical and civil engineering, architecture, and surveying, but they were not infallible. This survey of the route of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway by self-taught George Stephenson was riddled with errors which resulted in Parliament rejecting the first bill for the railway.

Why did some projects succeed and — more importantly — why did others fail?

Drawings often survive, not just for the objects that existed in our past but also for those that almost did. Plans of failed proposals can be just as illuminating as plans of the successful ones, providing valuable lessons for modern engineers.

Museums and archives around the world now take on the responsibility of preserving technical drawings as a record of our history.

Amongst the collection of the National Railway Museum in York are around 1 million mechanical, civil, and architectural drawings – ranging from the world’s first drawing of a steam locomotive from 1803 up to the latter parts of the 20th century.

Chris Valkoinen, Copy Services Assistant, National Railway Museum

Chris.Valkoinen@railwaymuseum.org.uk www.railwaymuseum.org.uk

All images ©National Railway Museum/Science and Society Picture Library

Christopher Valkoinen has written an illustrated book telling the story of how the railways changed the world, told using the engineering drawings from the museum’s collections. Railways: A History in Drawings is published by Thames and Hudson in association with the National Railway Museum.