NEC dispute resolution provisions

Claire King, Partner and Nicholas Gould, Partner, Fenwick Elliott

THE NEC4 Engineering and Construction Contract (ECC) made some major changes to the dispute resolution options when compared with the NEC3 ECC. Tellingly, these were rebranded ‘resolving and avoiding disputes’. This rebrand aligns with a key theme underlying all NEC contracts, namely proactively addressing issues as and when they arise during a project rather than letting them build up into a classic final account dispute at the end of the works. The major changes made to the dispute resolution options available include:

- The inclusion of a preliminary stage of meeting or meetings of the parties’ senior representatives in both options W1 and W2; and

- The addition of a third option (option W3) which involves a dispute avoidance board (DAB) that seeks to resolve ‘potential’ disputes before they become actual disputes. In this article we review these two key additions and ask what they add to the tools available to parties to ensure the prompt resolution of disputes (or potential disputes) as and when they arise.

Options W1 and W2: The addition of senior representative meetings

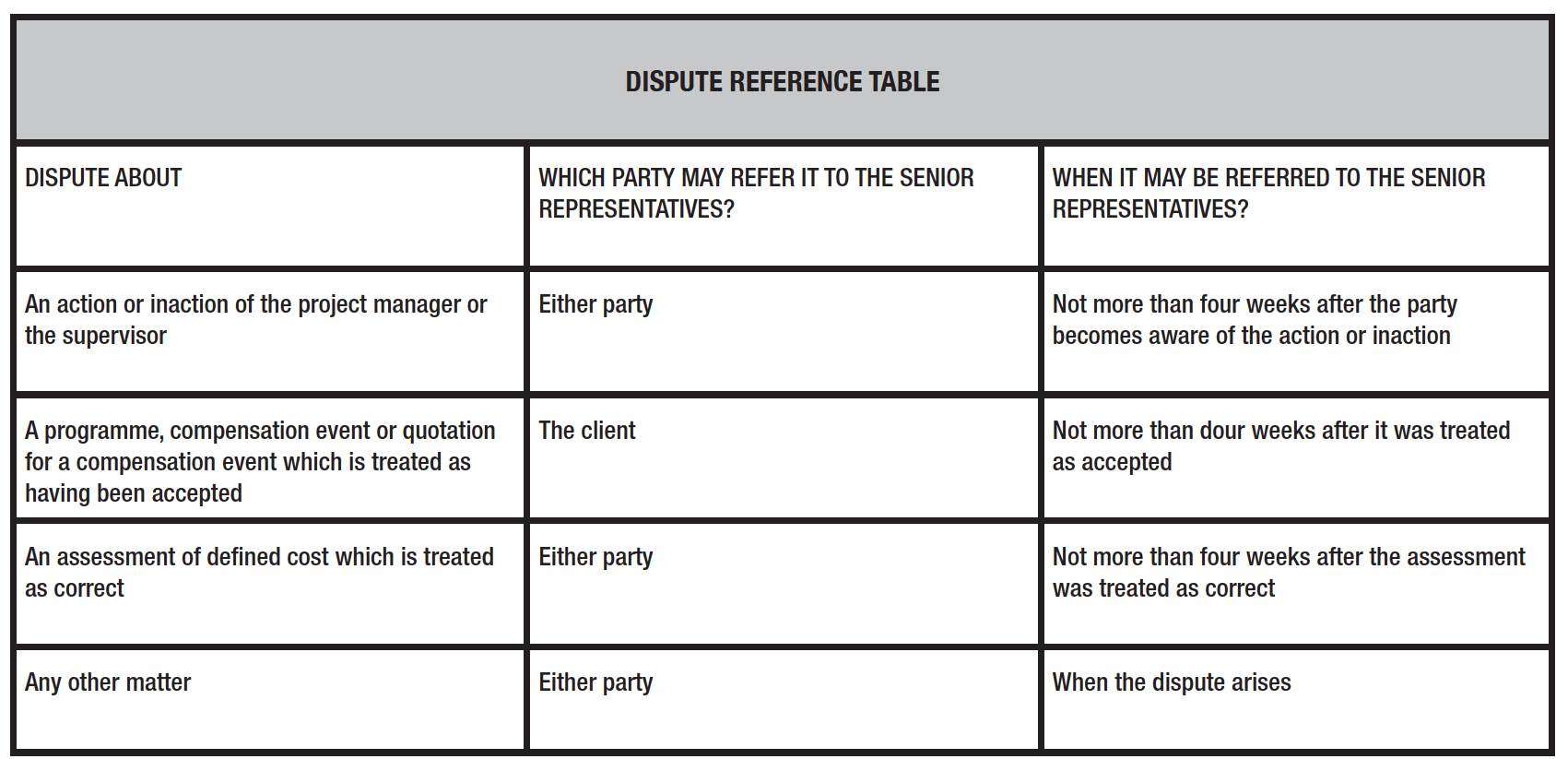

Figure 1.

It is now very common in construction contracts generally (as well as PFI contracts) to have an initial step in dispute resolution provisions which involves senior representatives of the parties meeting to resolve disputes. This makes sense as it is an opportunity to focus minds before matters (and costs) escalate further. Referring matters upwards can also (sometimes) remove the dispute from the politics that may be dictating how it is presented at a lower level of the project. Instead, the wider commercial relationship between the parties can be brought into play.

The provisions for senior representative meetings in options W1 and W2 of the NEC4 ECC are, however, very different in a number of ways. This is fundamentally because option W2 should be used where the Housing Grants, Construction and Regeneration Act 1996 (as amended) applies whereas option W1 only applies where the act is not applicable (i.e., outside of the United Kingdom). As construction practitioners in England and Wales will be aware, the act expressly provides that where the right to statutory adjudication applies, a party has the right to adjudicate on a dispute ‘at any time’. The act therefore limits the NEC’s ability to impose conditions precedent on starting any adjudication where it applies to the contract.

With this in mind, we first look at how the senior representatives’ discussions are provided for within option W1, where the act does not apply, before turning to option W2.

Option W1 – Where the act does not apply

Option W1 makes referring a dispute to senior representatives a condition precedent to referring a dispute to adjudication. A dispute cannot be referred to adjudication unless or until it has gone through the senior representative process. Senior representatives need to be set out in the contract data by the parties. Such a condition precedent is enforceable under English law1, albeit those working in different jurisdictions will need to consider the enforceability of this obligation separately if they wish to use this option.

The dispute reference table (Figure 1) sets out what dispute can be referred by which party. The one point on the table that is worth noting (and that may be contentious) is the restriction on who can refer disputes as to programmes, compensation events and quotations where they are ‘treated’ as agreed under the terms of the NEC. Translated, this means that they are treated as accepted because one party has missed a deadline and a deeming provision has kicked in2.

In light of the act there is also no deadline for referring any issues that are not agreed at the end of the process to adjudication.Whilst it is likely that the party disputing the deemed acceptance in the NEC4 form will be the client, we can see a situation where the contractor would want to refer that issue, especially where the project manager denied that the programme, quotation, etcetera had actually been deemed accepted. In practice, it could be that this was referred as ‘any other matter’ in the table above. However, we can also see a situation where the restriction on referral could in itself become contentious (albeit that the parties would hopefully act sensibly in such circumstances).

The procedure for the senior representatives’ meeting(s) itself is fairly straightforward. Parties exchange statements of case limited to ten sides of A4 together with supporting evidence. These must be provided within one week of a notification by a party that it wishes to refer a matter to senior representatives for a resolution3. Following the provision of statements of case, the contract provides for ‘as many meetings and use any procedure they consider necessary to try and resolve the dispute over a period of not more than three weeks. This makes sense, as complicated disputes often require separate discussions on each issue, following which further work can be carried out to try and narrow parties’ differences.

At the end of the process the senior representatives put together a list of issues that are agreed and not agreed. The parties should then put into effect the issues that are agreed. For the issues that are not agreed, either party then has two weeks to refer those 3 Clause W1.1 (2) matters to adjudication4. If they don’t refer the issues that are not agreed within that time period, and the two-week period isn’t extended before the deadline by agreement, then neither party can subsequently refer to the matter to adjudication. This is a time bar provision which is clearly set out with both a clear deadline and consequences. As such, certainly under English law (and absent any circumstances giving rise to a waiver or estoppel), it should be enforced. Accordingly, the parties need to be very aware of the consequences if they don’t act quickly and initiate an adjudication following the senior representatives finalising the list of agreed and disputed issues5.

Given the fact that disputes can arise fairly easily when you apply this test, one can easily see circumstances where a dispute is artificially labelled a ‘potential dispute’ despite the issue constituting a dispute under guidance.Option W2 – Where the act applies

The procedure for the senior representatives’ meetings under option W2 is different in one crucial respect – it is optional. Either party can still adjudicate ‘at any time’ in accordance with the act. Given the broad definition of a ‘dispute’ there is also no limit placed on what dispute can be referred to senior representatives as there is in option W2. In light of the act there is also no deadline for referring any issues that are not agreed at the end of the process to adjudication, as seen in option W2. Instead, a party must issue a notice of dissatisfaction within four weeks of receiving the adjudicator’s decision or it will become binding on them6.

Option W3: The introduction of dispute avoidance boards (DABs)

As with option W1, option W3 does not apply where the act applies to the contract. This will obviously apply to large swathes of construction contracts in England and Wales unless they fall under the statutory exemptions.

What is provided for?

As outlined above, the new option W3 provides for the appointment of a DAB, to deal and try to resolve ‘potential’ disputes before they crystallise into disputes. If this fails, then a dispute can be referred to the tribunal (either the courts or arbitration) provided that a notice of dissatisfaction has been given in relation to the DAB’s recommendation within four weeks of receiving notification of that recommendation7.

The DAB can be made up of either one or three members and they are meant to be appointed at the starting date of the contract. If the parties don’t appoint anyone or can’t agree on who to choose then a referral can be made to the DAB nominating body (typically the ICE who publish the NEC form). The role of the DAB is mean to be an active one, with regular site visits encouraged and provision for the DAB to be provided with the contract, progress reports and ‘any other material they consider relevant to any difference which they wish the DAB to consider in advance of the visit to site’8.

If there is a difference or potential dispute, then the DAB is meant to assist in resolving the issue before it becomes a formal dispute. At the end of a site visit it should then provide a recommendation as to the resolution of the difference. If the parties wish to dispute that recommendation and take the issue to the tribunal then they need to issue a notice of dissatisfaction within four weeks. As is commonplace where there is a DAB or adjudicator involved prior to final determination of a dispute in the courts or arbitration, the DAB cannot be called as a witness in later proceedings.

What does a DAB add to a project?

Parties are paying for the DAB in order to avoid disputes and maintain good relationships between the parties during the job.There is substantial evidence from the adoption of similar DABs pursuant other contract forms (the most famous being in the International Federation of Consulting Engineers (FIDIC) forms) that having such a resource can be good value for money in high value and complex projects if they work as intended to reduce the build of issues into disputes during the projects. By encouraging parties to manage their risks effectively rather than get bogged down in allegations projects can finish earlier and unnecessary costs can be avoided.

For example, the Dispute Resolution Board Foundation (DRBF) website highlights the following figures in relation to the financial benefits of dispute boards in Australia and New Zealand:

“The value of Australian and New Zealand projects utilising dispute boards (DB) is now approaching $18bn, most of that having occurred since the formation of the Dispute Resolution Board Australasia (DRBA) in mid-2003. The Australasian projects which have adopted the DB process have all involved complex technical work conducted under extreme risk allocation arrangements with tight completion targets and substantial liquidated damages for late completion. Notwithstanding the demanding contract conditions, the Australian industry statistics to date (as of July 2014) are impressive and reflect the recorded experience of a variety of international legal and cultural systems:

- More than 80% of DB projects have finished on or ahead of time compared to the industry norm of well under 60% for similar value projects without DBs. The majority of DB projects have also been completed within the owner’s budget.

- Less than 5% of DB projects have been more than three months late, compared to the industry norm of more than 25% for similar value projects without DBs.

- Just under 80% have been completed without a single referral to the DB, compared with an industry norm for projects without DBs of less than half that percentage completed without off-site dispute resolution processes being invoked.”9

As such parties are paying for the DAB in order to avoid disputes and maintain good relationships between the parties during the job. This encourages a successful project. However, using the DAB in the way envisaged (i.e. with regular site visits and updates) is likely to be fairly expensive even where the DAB has only one member. As such this option is only suitable for fairly high value projects, where the costs of having the DAB are more proportionate to the potential benefits of having an impartial individual or body that can act as an arbiter should any differences emerge between the parties.

What is a potential dispute?

One other nuance is how easy it is to distinguish between a difference which is not yet a dispute and a dispute. The classic test for a dispute was set out by Mr Justice Jackson (as he then was) in AMEC Civil Engineering Limited v The Secretary of State for Transport (2004) EWHC 2339 (TCC) and is as follows:

- “The word ‘dispute’...should be given its normal meaning. It does not have some special or unusual meaning conferred upon it by lawyers.

- Despite the simple meaning of the word ‘dispute’, there has been much litigation over the years as to whether or not disputes existed in particular situations… the accumulating judicial decisions have produced helpful guidance.

- The mere fact that one party (whom I shall call ‘the claimant’) notifies the other party (whom I shall call ‘the respondent’) of a claim does not automatically and immediately give rise to a dispute...that a dispute does not arise unless and until it emerges that the claim is not admitted.

- The circumstances from which it may emerge that a claim is not admitted are protean. For example, there may be an express rejection of the claim. There may be discussions between the parties from which objectively it is to be inferred that the claim is not admitted. The respondent may prevaricate, thus giving rise to the inference that he does not admit the claim. The respondent may simply remain silent for a period of time, thus giving rise to the same inference.

- The period of time for which a respondent may remain silent before a dispute is to be inferred depends heavily upon the facts of the case and the contractual structure. Where the gist of the claim is well known and it is obviously controversial, a very short period of silence may suffice to give rise to this inference. Where the claim is notified to some agent of the respondent who has a legal duty to consider the claim independently and then give a considered response, a longer period of time may be required before it can be inferred that mere silence gives rise to a dispute.

- If the claimant imposes upon the respondent a deadline for responding to the claim, that deadline does not have the automatic effect of curtailing what would otherwise be a reasonable time for responding. On the other hand, a stated deadline and the reasons for its imposition may be relevant factors when the court comes to consider what is a reasonable time

- If the claim as presented by the claimant is so nebulous and ill-defined that the respondent cannot sensibly respond to it, neither silence by the respondent nor even an express non-admission is likely to give rise to a dispute for the purposes of arbitration or adjudication.”

Given the fact that disputes can arise fairly easily when you apply this test, one can easily see circumstances where a dispute is artificially labelled a ‘potential dispute’ despite the issue constituting a dispute under the guidance above. It seems likely that the wording in clause W3.3. (1)10 would make it necessary to refer even an obviously crystallised dispute to the DAB before it went to the final tribunal in order to avoid any issues as to jurisdiction. That could be frustrating in some circumstances albeit the parties can always agree to refer matters straight to the tribunal as a way around this.

Summary

The NEC4 options for ‘resolving and avoiding disputes’ provide some useful additional dispute resolution tools for encouraging the early resolution of disputes particularly where the act does not apply. Where the act does apply the provision for referring matters to senior representatives is essentially voluntary. In our experience parties often take this step voluntarily for large and complex disputes anyway before hitting the adjudication button. However, there is never any harm in reminding parties to engage in discussions in relation to disputes, particularly where the legal and expert costs involved with taking the next steps can be high.

As to the provision of a DAB, this allows the NEC4 to try and compete with the FIDIC forms, which already provide for similar boards, and which are increasingly popular on large and high value projects internationally. It seems unlikely that option W3 will be used much in England and Wales given the act, its fairly limited exceptions and the popularity of adjudication as a familiar and quick dispute resolution process in this jurisdiction generally.

Claire King, Partner and Nicholas Gould, Partner, Fenwick Elliott

www.fenwickelliott.com @FenwickElliott

---

1 See Emirates Trading Agency Llc v Prime Mineral Private Ltd (2014) EWHC 2104 (Comm)

2 For example, see clause 31.3 where a project manager fails to notify acceptance or rejection of a programme and then fails to respond when a further notice is issued. Alternatively, clause 62.6 which deems a quotation accepted in certain circumstances

4 Clause W1.3

5 The key House of Lords case of Bremer Handelsgesellschaft GmbH v Vanden Avenne-Izegem nv (1978) 2 Lloyd’s Rep. 113 held that these will be considered to be conditions precedent and will be binding only if: (a) the clause states the precise time within which the notice is to be served; and (b) it makes plain by express language that, unless the notice is served within that time, the party making the claim will lose its rights under the clause

6 Clause W2.4 (2)

7 Clause W3.3

8 Clause W3.2 (4)

9 Concept (drbf.org.au) as downloaded on 30 June 2022

10 ‘(a) A Party does not refer any dispute under or in connection with the contract to the tribunal unless it has first been referred to the Dispute Avoidance Board as a potential dispute in accordance with the contract’